Changing the context

By Antonio Buehler

“Hello, Kenton,” I said to the eleven-year-old seated across from me on the floor. [1] He sat slouched over, avoiding eye contact, staring at the shoe on his extended leg, a seeming warning not to get too close. I asked him why he was interested in joining our education community. He did not have an answer, but he was eager to share that he had “really bad teachers” at his prior school. “No one took the time to listen to me,” he added.[2]

After a long pause I asked him what he likes to think about. “Robots,” he answered, “I had an idea about why robots will take over. Humans can’t contain emotions.” He added that Star Trek was not a perfect human society because “humans have a lot of problems.” When I asked what could lead to an improved society, he raised social justice issues. He was most concerned about police brutality and colonization, and he wanted to learn more about those issues at Abrome.

At Abrome, the Self-Directed Education community I spend my days at, we have limited time to build relationships with young people. We reject the designation of school, just as we reject most of the practices and structures of schooling; but similar to school, we are a place where young people spend six hours a day, for about 180 days a year, for up to 13 years. That is a lot of time, particularly if someone is forced to spend it where they do not want to be, yet it is only about 20 percent of their waking hours in a given year.

Families who seek us out tend to fall into one of two camps. The first consists of those who are running toward us, most often with a focus on finding a liberatory environment where young people can practice freedom on a daily basis. It is with the young people in this camp that we often have the luxury of time, as they tend to stay with the community long-term.

The second consists of those who are running away from something that has deeply harmed their children, although sometimes they are just hoping to stop the compounding violence of schooling that amplifies other forms of trauma. This camp tends to be more focused on emancipation from a harmful institution. In large part, we are seen as a trauma center for families that have run out of options. But we want to do more than just stop the bleeding; we want to assist healing. Too often though, when the bleeding stops, with comfort knowing that the worst is behind them, the family moves on, sometimes reintroducing their kids into the same environments they were running away from in the first place.

Without the certainty or luxury of time, but freed from the constraints of trying to shape young people into some idealized adult vision of what they are to become, we focus on changing the context instead of changing the individual. Changing the context is the quickest and easiest way to support young people no matter the level of distress in their lives.

Opt out

I met Barb and her 15-year-old son, Devin, at the local coffee shop. I introduced myself to Devin, but he just stared at the table in front of him. Barb explained that Devin had recently been hospitalized and needed to find an alternative school as soon as possible because of the harm that school was causing him. I turned and asked Devin if he wanted to leave school. Keeping his head down, he said nothing. I told Barb, “he doesn’t have to go back to school tomorrow.” I explained that finding a new school was secondary in importance to stopping the pain, which she could do by withdrawing him from school immediately. Devin looked up and said, “I would like that.”

Dominant culture believes children cannot be trusted to make their own decisions; if left to their own devices, they will derail their futures. Therefore, by way of parenting and schooling, children must be guided into adulthood. Although the manner of parenting (e.g., authoritative, authoritarian) and schooling (e.g., progressive, classical) that is accepted is not uniform, control over children is the narrative that society has internalized, and it has become so entrenched that opting out seems radical.

Baked within the conventional assumptions of what parenting and schooling should be is a belief that children are not capable of understanding what is in their own best interests. These beliefs are too often the justification for ignoring the cries for help or relief from young people, which ultimately leads many children to completely withdraw from meaningful engagement with their families and the communities around them.

Individually scrutinized, the generalized beliefs around conventional parenting and schooling can be seen as absurd on their face. Does a child need to be able to sit quietly for long periods of time around adults? No. They could be free to play, so long as guardians are not wedded to the belief that children must be docile. Do they need to learn to read by the age of five? No. They could learn to read when they are ready, so long as they are not placed in environments where they are ranked against same-age peers.

But even when we pick apart the individual arguments, people still revert to a general faith in adults wielding power over young people, arguing that we should just tweak or remove the more absurd practices, instead of recognizing that power over is the root absurdity. The first step to changing the context can be acknowledging that conventional parenting and schooling are nothing more than harmful belief systems that have been conditioned within us, and that opting out is a possibility.

A month later, Barb gave me an update. She took my advice and withdrew Devin from school, allowing him to stay home, and she believed it saved her son’s life.

Personal autonomy

Stephanie told me that her autistic child Zachary was in a constant state of distress at school, and that he would bring that distress home to the family each afternoon. Stephanie first tried to advocate for accommodations at the local public school, and when that did not work, she enrolled him in the most progressive school she could find. Yet she still found herself physically prying his fingers from the door frame each morning to go to school, while trying to find ways to ameliorate the compounding symptoms of physical illness that seemed to stem from the stress. Zachary felt trapped in environments where he was expected to contain his emotions, ideas, and movements so that the adults could feel comfortable.

When young people are in distress, adults often attempt to help the child manage through it. This rarely serves to benefit the child as the causes of the distress are usually external. Depending on their identities and places of being, young people can be impacted by the wide variety of social, economic, and legal forms of oppression that adults face. Additionally, other than those who are incarcerated, no group of people are more routinely denied autonomy over their bodies and minds than young people. Autonomy is a basic human need, and distress in response to violations of that autonomy is not a defect of the child. We can change the context for these young people by removing the oppressive practices and structures that are placed upon and inhibit the autonomy of children.

Removing such practices and structures requires self-reflection on the many ways that we as adults police young people for the sake of convenience. Whether we head to work while we send kids to school, or we stay at home and allow children to roam unschooled, we tend to make decisions for them with our own needs or the needs of people other than our children in mind. From an efficiency perspective this can make all the sense in the world. Young people are more impulsive than adults, and are less likely to abide by social norms, especially social norms that prioritize docility in young people. If the goal is to minimize social disruption or move everyone along a similar path (e.g., classroom activities) then tolerance for individual deviations from the group quickly wanes. But what makes sense to those with power in terms of efficiency can lead to terrible outcomes for individuals, with many historical examples of the worst of outcomes when efficiency over autonomy becomes institutionalized and systematized.

A more nuanced debate about the limits of autonomy may be warranted when it comes to culture building within groups. It serves everyone’s interest within a group to be able to feel safe, necessitating that each person consents to being a member, and that there are agreed upon boundaries that each member honors. Boundaries often include expectations of or limitations on ways of being (e.g., noise, eye contact, active participation). The challenge for young people is that they do not get to choose their family, they are often placed in communities against their will, and they typically lack the resources needed to navigate out of spaces that violate their autonomy. Understanding this lack of power, adults must endeavor to strictly limit any encroachments upon personal autonomy to only those that are necessary for the well-being of a consent-based community, or to protect the autonomy of others. We must scrutinize the many generally accepted expectations of or limitations on young people that are not reasonable, such as demands for performance and productive output, controls on movement (e.g., stimming), and notions of respectability. And bodily integrity should be non-negotiable. We must also provide ways for young people to opt out of situations where they perceive their autonomy would be unduly inhibited.

Stephanie’s decision to move Zachary from environments that disregarded his personal autonomy to one that openly acknowledged it resulted in many of Zachary’s struggles quickly disappearing, and the quality of his life and that of his family improving substantially. For example, the tussling each morning at the door disappeared, allowing Zachary and his entire family to avoid a stressful event at the beginning of the day, which helped head off a cascade of follow-on crises.

Acceptance

After our morning meeting on Gabriel’s first day, he asked if he could play video games. I said, “yes, you get to decide how you spend your time here.” Thirty minutes later I was walking through the space and I noticed a cable running from an outlet into a closet. I knocked on the door and heard, “come in.” I opened the door and saw 14-year-old Gabriel on his knees playing on a laptop. I asked if everything was alright, and he said it was. I asked if he wanted to interact with others, and he said he preferred remaining in the closet. He stayed there until the end of the day.

Gabriel’s routine continued day after day. The other Facilitators and I became more and more concerned that perhaps we were not properly supporting someone who chose to wall himself off in a closet for the entire day, each day. Our schoolish lens had us worried about missed opportunities for development, as well as possible questions from his mom about how he was spending his time. We chose to push down our insecurities, prioritize being welcoming and inviting, and honor his desire to be by himself.

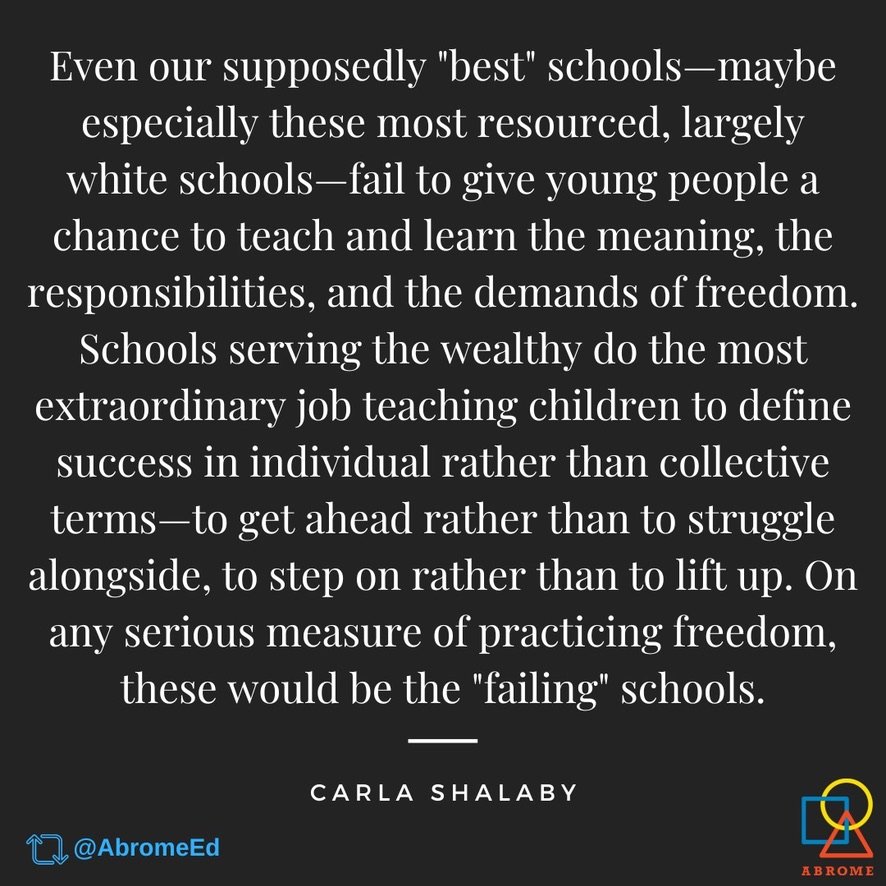

We live in a society predicated on hierarchy. We judge others (and ourselves) by where they fall within various hierarchies. And where they fall determines to a large degree what access, privileges, and so-called rights they have. The pyramid structure of society requires large numbers to fill out the base so that a select few can benefit from their place near the apex. In other words, most people have to be labeled as losers in order to justify the outsized gains of the winners in an ostensibly meritocratic society. We see these hierarchies in most all economic, legal, political, and social institutions. These hierarchies not only determine who benefits and who exist to serve those who benefit, they also perpetuate and reinforce the unjustness of other existent hierarchies (e.g., white supremacy, ableism).

Young people are not immune from the impacts of hierarchy. In fact, hierarchy is a primary force in shaping them. As an oppressed group with negligible economic and political power, they are seen by government and industry as raw material to be molded into reliable workers and consumers (the base), while their family often encourages a climb to the top. Because the aforementioned groups are constantly measuring the youth (e.g., grades, athletic performance, leadership positions) in an attempt to rank and sort them, young people learn quickly how they measure up to their same-aged peers.

Unfortunately, the cloud of competition leads to a denial of self, as ways of being become scrutinized and used as inputs for placement within hierarchies. While families with sufficient material resources may find ways around it, children who are considered too far below or behind arbitrary behavioral or performance norms are often singled out and treated as defective. Children whose identities are not idealized by dominant society (e.g., Black, Indigenous, trans, undocumented, autistic) risk amplified marginalization.

Because of the unforgiving nature of the pyramid structure of society, young people must expend significant energy masking their emotions to ward off scrutiny from adults in positions of power. This harms young people in the moment and in the future, as it forces them to ignore their most basic needs, denies them meaningful relationships, and hinders their natural development. Adults can change the context by accepting the child for who they are and their ways of being. Acceptance allows for the emergence of psychologically safe spaces where children are free from assessment, judgment, or ridicule. Instead of declaring what is important and then measuring it, adults can trust kids to take what they need.

The closet door in many ways was a physical boundary that Gabriel used to protect his emotional boundaries. And for perhaps the first time in his life, Gabriel’s boundaries were honored. Like many young people who have been wounded both in school and in their personal lives, Gabriel did not need to be pushed into activities or behavior that made adults feel comfortable—he needed to be accepted for who he was in the moment, and to have his needs centered. After a month, Gabriel left the closet for good, and fully embedded himself at the heart of the community.

Question authority

During one of our twice-weekly Flying Squad days, we stopped by the Texas State Capitol. Flying Squads is an intentional effort to support young people in reoccupying public space in an anti-child society. The young people I was with chose to explore the grounds, and 20 minutes later Kenton and Harriet came back to tell me that they had been kicked out of the Visitors Center. I asked why and they said because they were without a chaperone.

Children are oppressed in contemporary society in part because many ostensibly well-intentioned adults believe oppressive practices are necessary to prepare children for an unfair world. This is shortsighted on two accounts. First, oppressing children doesn’t better prepare them for future oppression. Abuse wears people down, forcing them to expend limited personal resources trying to minimize, resist, or escape it. Second, oppressing children seeds future oppression. It is easier for people who have internalized the oppression of one group (i.e., children) to rationalize harming others (e.g., the houseless, BIPOC) or supporting institutions that do (e.g., capitalism, white supremacy). And simply having been oppressed in the past is not automatically some form of inoculation against being willing to accept the oppression of others, particularly when people get to graduate into the class of the oppressor (i.e., adulthood). Adults can instead engage in the struggle of youth liberation.

Youth liberation compels us to change how we interact with kids. But it also requires that we go further by using our relative privilege to alter the ways that other people and institutions interact with young people. One of the most powerful methods of doing so is to question authority. We must start by critically examining whether forms of authority are ethical, the ways in which authority is established (or imposed), and how authority is perpetuated. Then, we need to identify ways to subversively challenge that authority.

When we interrupt child oppression, young people see that we stand in solidarity with them. We change the context. We let them know that just because we are free from the age-based discrimination they face does not mean we do not concern ourselves with their struggle. We let them know that their experiences and their lives matter to us. And that recognition can open up conversations about how liberation is intertwined, how none of us are free until all of us are free, and how we can support the liberation of others. In this way we not only stand up for them, and children everywhere, we seed in them the capacity to stand up for others.

When I walked into the Visitors Center with the young people in tow, a member of the staff and a security guard met me at the main desk. I asked why they kicked the young people out of the center. With the young people listening intently, I wanted to model how we can question authority. The staff member said they were worried about kids being in the building without an adult. I told them that we believe that young people have as much of a right to navigate public space as adults do.

Their supervisor then joined us at the desk and stated that it was policy that children have a chaperone with them. When I asked to view their policies, she told me that it was not written down as a policy, but it was instead a commonly enforced practice. I pointed out that since it was not a policy, that they did not have any right to restrict these kids from being able to roam unaccompanied through the center. The supervisor then asked who would be held liable if the kids injured themselves or damaged something. I said I would be. I then turned toward the young people and told them to enjoy themselves. Kenton's eyes met mine while I was saying it, and he smiled. Then Makayla, recognizing that everyone was still standing around, said, “alrighty,” and off they ran.

Place within society

I looked out the window and saw Kenton, Leo, and Raj about 50 yards away playing in the grass. Then I saw seven-year-old Leo, who was visiting as a prospective member of the community, throw a large rock into the road. I walked outside to have Leo remove the rock from the road and to bring everyone back to Abrome. I then turned to Kenton, who was a few years older than the others, and said, “we need to take care of each other.” He replied, “I’m not a babysitter.”

I asked Kenton, who had only been with us for a couple of months, if he felt he had any obligations to others. Kenton changed the topic and said that he was upset because this was supposed to be an “activist school” and that he did not feel as though we were doing enough in the community. I responded that we were trying to create something that went beyond protesting or getting arrested. I explained that we were trying to live prefiguratively, meaning we were trying to organize and engage with each other in ways that not only allowed us to navigate and improve the society we live in, but to model the relations that a better future society would entail.

Why should young people believe that this world is for them? They cannot vote even though the consequences of political decisions will most often impact them more than any other age group, as they are the ones stuck with laws and policies the longest (because older generations die off). In sick societies that value wealth accumulation over collective well-being, this leaves younger and future generations with the burden of reckoning with legacies of human rights violations, dispossession, poverty, and environmental degradation.

Young people also have limited control over their own bodies. Thanks to compulsory schooling laws, kids are situated in environments where they are forced to compete against peers on measures that often have no meaning to them, and subjected to punitive rules that regulate everything from what they can wear to when they can talk. The lack of bodily autonomy also extends beyond the schoolhouse. They are age-limited on employment options, and the number of hours they can work “when school is in session.” At home, even in cases where young people are being abused, states prohibit children from emancipating themselves until their mid- to late-teens, and then only if they are self-supporting, which is an impossibility for most because of the restrictions placed on youth employment. And even in the most supportive of homes, kids are unable to access certain types of healthcare (e.g., birth control, vaccines) without the permission of their parents or guardians.

While youth liberation can seem like a fantastic delusion at times, particularly from the point of view of young people, we can help them reconceive their place within society, and support them in acting on society, so that they can take ownership of changing the context of their lives and of the world around them. We may not be able to liberate them by ourselves, but it can be liberating for them to realize that we trust them to not only make decisions about how they spend their time and what their education looks like, but also to engage with the world in order to alter it. Being able to live what we want to create in the world can be the most liberating feeling of all.

Two weeks later, we dedicated our tri-weekly field trip day to supporting the houseless community, spurred primarily by a vicious public backlash by rightwing groups to the Austin City Council decriminalizing houselessness. The decision was a personal one for one of the kids, who had been houseless the year prior. We made hundreds of lunches and a large pot of soup, and went to three houseless encampments in the city to distribute the food. Many of the young people got into extended conversations with the houseless folks, particularly Kenton, Harriet, and Olivia. The experience allowed them to feel as though they could take action to materially improve the lives of people beyond themselves.

Moving on

Kenton had joined us in the fall of 2019, hoping to put an end to a string of bad schooling experiences. While I was shocked by how he had been treated at his prior schools, it was learning about the trauma he faced in his personal life that really floored me. That trauma helped explain many of his initial difficulties: defensiveness, angry outbursts, an unwillingness to trust others, and dissociation when stressed. But, by changing the context in all the ways mentioned in this essay, over the span of about half a year, he slowly learned to trust us, trust in himself, and trust that he could improve the world around him. Unfortunately, once the pandemic hit in 2020, he had to move out of state to be closer to family.

Changing the context has an outsized (arguably the greatest) impact on the quality and direction of the lives young people. Parents and guardians have about 18 years to support children, while caregivers and educators have far less time. While we can lament the years children may have needlessly suffered through the expectations and limitations of dominant society, today will always be the best day to change the context.

[1] This essay is a work of nonfiction. Names, genders, and some descriptive details have been altered to protect the privacy of individuals.

[2] This essay was originally published in the book Trust Kids! Stories on Youth Autonomy and Confronting Adult Supremacy, edited by carla joy bergman, AK Press (November 2022).