WHEN ASKED "What do we need to learn this for?" any high-school teacher can confidently answer that, regardless of the subject, the knowledge will come in handy once the student hits middle age and starts working crossword puzzles in order to stave off the terrible loneliness.

~ David Sedaris

I love this line from David Sedaris.

Not gonna lie, being able to solve the Sunday NYT crossword puzzle is an impressive trick to show off. One does not need to spend 15,000 hours in school to get there though. Simply reading and being engaged in the world is a great, often better alternative.

But it is the end of the line that packs the punch. “To stave off the terrible loneliness.” We certainly have a loneliness problem in the US. One report suggests that 61% of young adults and 51% of mothers with young children feel “serious loneliness.”

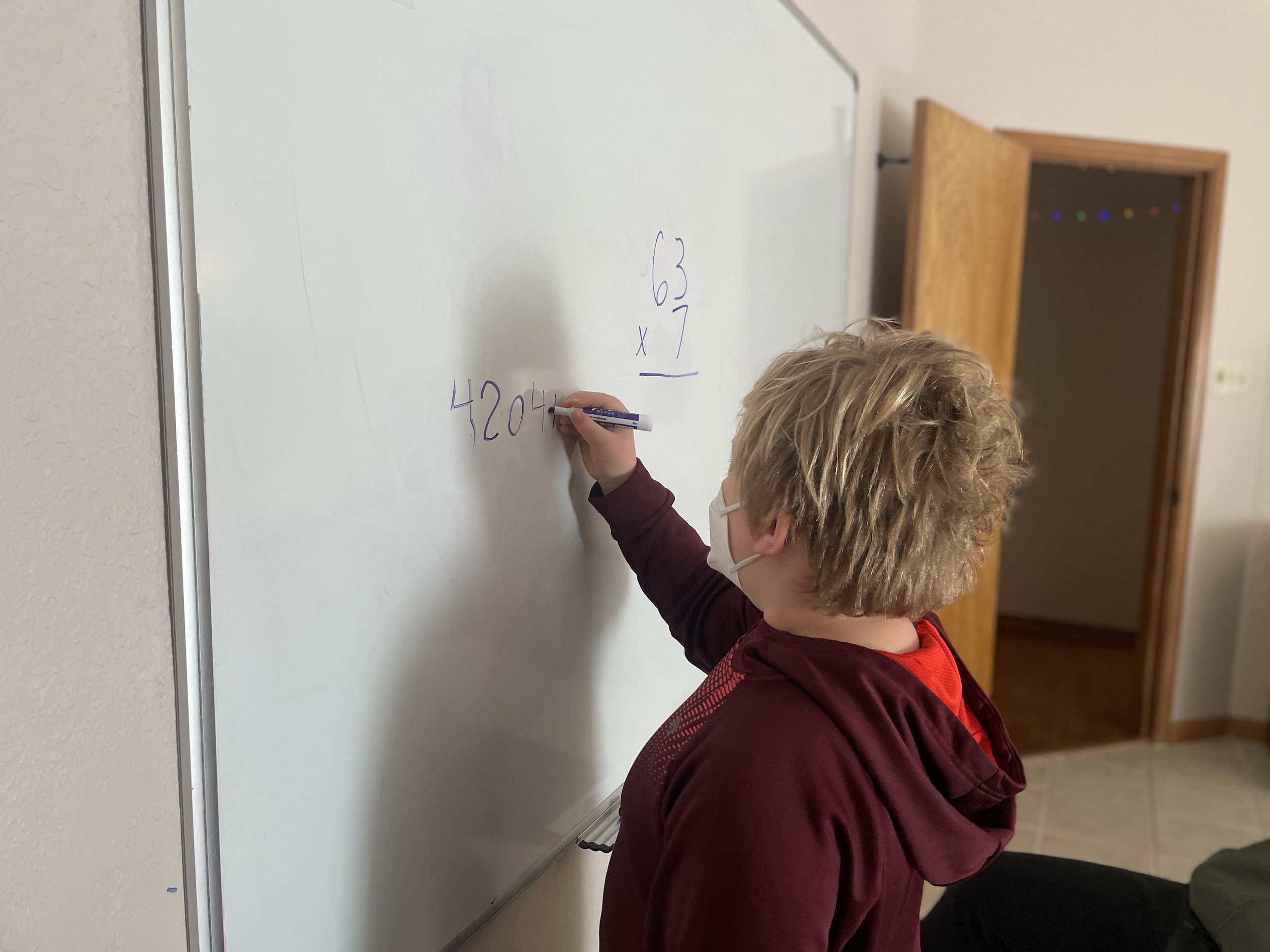

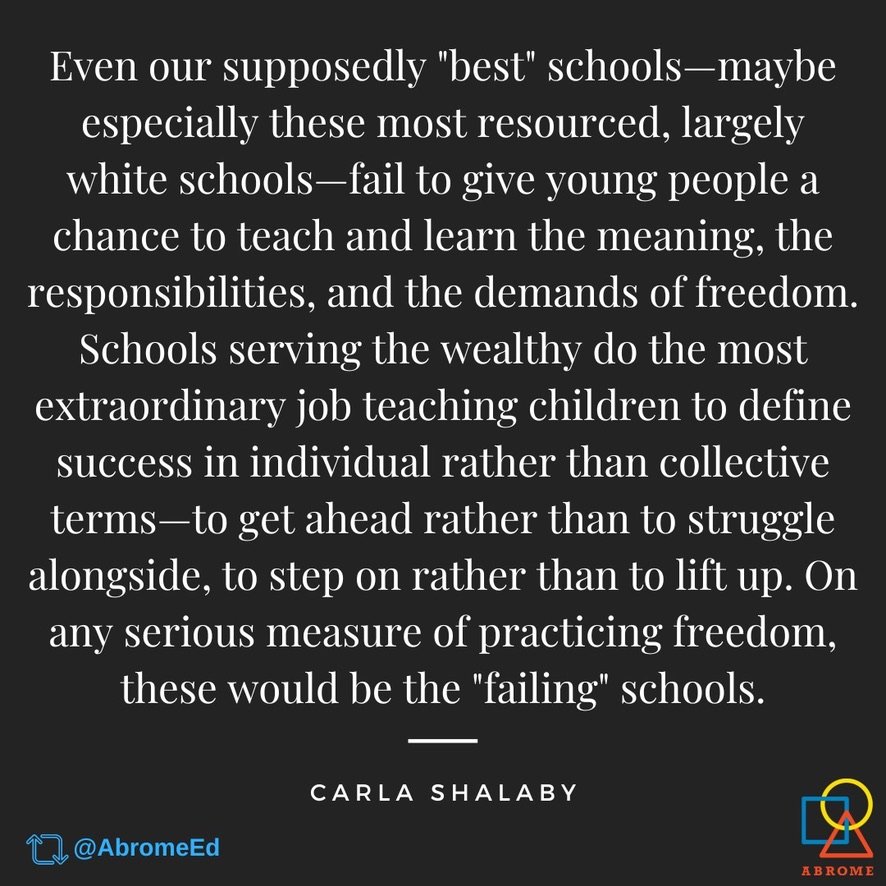

Such widespread loneliness is not a feature of human existence, it is a feature of modern, schooled society, where young people are segregated from life and forced to compete against their peers on almost entirely useless tasks for 15,000 hours of their young lives, so that they can then compete against others in college, and then against more people in the workplace.

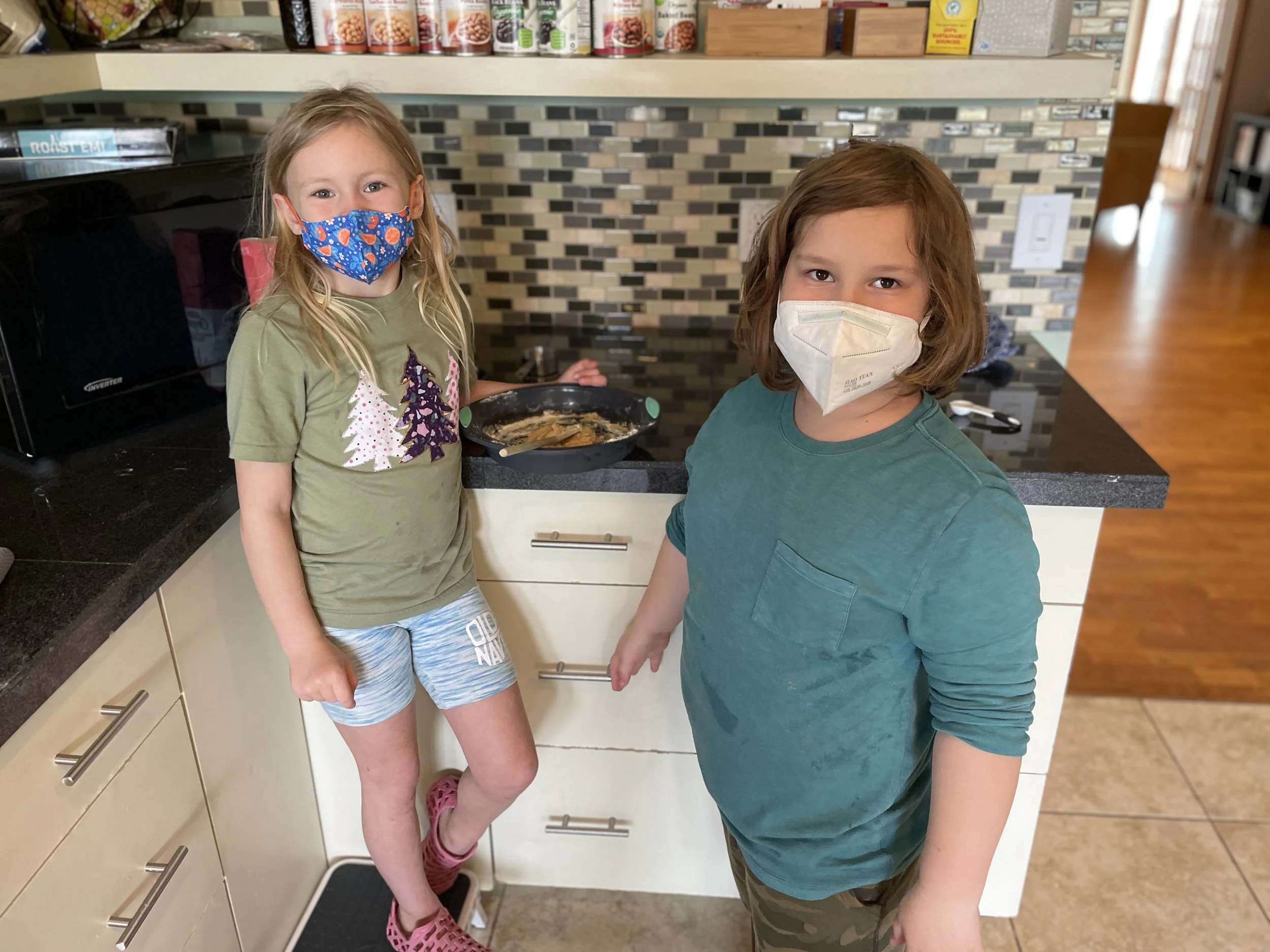

Very few young people get to experience what community feels like, where the existence of others allows us to support and be supported. When young people are exposed to such environments they begin to value themselves and others simply for being, not for how they perform against others. And those young people are more likely to grow into adults who commit to cultivating communities of care.

Community is an antidote to terrible loneliness. Schooling is not.

—

Cover photo by micheile henderson on Unsplash