When people ask us what type of school Abrome is, or how we differ from other schools, we remind them that we are not a school. Abrome is an alternative to school. Abrome is Emancipated Learning.

Every public school in America is fundamentally the same, as are 99.8% of private schools. They operate on a coercive model of command and control schooling that prioritizes conformity and obedience over learning. They believe students are incompetent learners that need to be taught by knowledgeable adults. They rely on standardized curriculum. They believe that students must be constantly assessed, tested, and measured against same-aged peers. They believe that competition is the appropriate way to distinguish the intelligent and hardworking students from the stupid and lazy ones. They value students for the dollars they bring in, either seat-time revenue or tuition, as opposed to the value young people can provide to society.

Of course many of those schools will insist that they are different from the failed traditional schools that most young people are subjected to. Some are charter schools. Some are private schools. Some are even alternative schools! Instead of restrictive, standardized curriculum, those schools might claim that their students get to engage in personalized learning, meaning students are allowed to rearrange or stretch out certain aspects of their standardized curricular requirements. Or perhaps they will give lip service to peer learning and flipped classrooms as a way to suggest that they do not have an authoritarian, adult-directed schooling environment. Some schools may even eschew quantitative assessments for seemingly more compassionate qualitative assessments. But these efforts are nothing more than attempts at articulating differentiation (in name only) of the commodity known as schooling.

If schools cannot distinguish themselves with an educational fad (e.g., personalized learning), and because schools are all largely the same, they are left relying on and promoting superficial differences to convince families that they are better than other schools. These are called bells and whistles. Bells and whistles can be the promise of personalized learning, peer learning, flipped classrooms, or qualitative assessments. It can be technology in the classroom, with online academic support at home. It can be the promise of access to mentors and internships. It can be programing classes or maker labs. It can be an award winning yearbook club, robotics club, debate team, or science Olympiad team. It could be a 30,000 seat football stadium, an Olympic sized pool, or a 9-hole golf course. But what does not change with these bells and whistles are the underlying structures and practices of schooling.

Abrome is often described by what we are not. We are not a school. We do not replicate or perpetuate the structures and practices of schooling. We do not have teachers, classes, instruction, curriculum, testing, homework, grades, or age-based segregation. And there is good reason for us not replicating what is happening in school—schooling harms children. Schooling convinces most students that they are incompetent, stupid, untrustworthy, lazy, and inherently flawed. These students’ lives are substantially altered for the worse because of schooling. From a societal perspective, schooling destroys more human capital than any other institution. A small minority of school students do not become convinced that they are damaged goods, and instead fall into the trap of believing that they are inherently better than everyone else. This is also harmful to society, as students with a belief of superiority often assume positions of power and make decisions with little regard or understanding for the general public.

While eliminating the structures and practices of schooling is necessary, it is not sufficient to create a society where everyone is able to lead a remarkable life. Abrome goes beyond eliminating the harmful aspects of schooling by leveraging our Emancipated Learning model. Emancipated Learning is not an adornment, it is a fundamentally different approach to education based on the axiom that young people are competent and active knowledge seekers. We trust young people to take charge of their educational experiences and their lives.

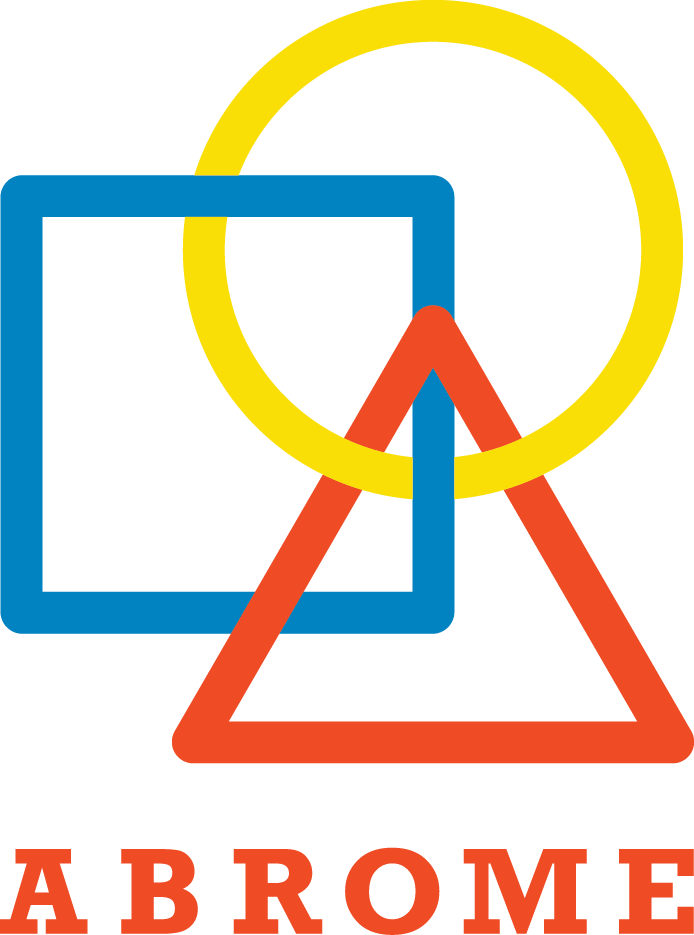

The Abrome logo provides a visual representation of how the Emancipated Learning model works. The Abrome logo is an adaptation of Borromean rings, which are an arrangement of three interlocked circles, with no two circles being interlocked. This is a form of a Brunnian link. If one were to break one of the rings in a Brunnian link, the other rings would fall away. Borromean rings show strength in unity, as the whole is much stronger than the sum of its parts.

The Abrome logo consists of a triangle, a square, and a circle, all in different colors, as opposed to three symmetrical rings. This was done to emphasize the importance of diversity in the Abrome space.

Well-being:

The circle in the Abrome logo stands for well-being. The circle is the best representation for a focus on the whole child. The circle has no end and no beginning, but it is reflective of the iterative or cyclical aspects of life such as personal growth and understanding. The circle draws people toward the center, just as we want Learners to look inward.

At Abrome, the well-being of Learners comes first. We recognize that in order for Learners to engage in deep, meaningful, and enduring learning experiences, they must first be happy and healthy.

Self-directed learning:

The square in the Abrome logo stands for self-directed learning. The square is the most flexible of the three shapes, which comports with the agile and adaptive approaches one must take to learning and discovery. The square is the best way to visualize the construction of knowledge using multiple dimensions. Whereas a circle draws you inward, a square invites you to investigate it from end to end.

Abrome Learners choose for themselves the activities and experiences they engage in. They embrace the responsibilities of learning and life.

Learning community:

The triangle in the Abrome logo stands for the learning community. The triangle is a rigid object that does not easily buckle under stress. The triangle symbolizes how the learning community provides strength to individuals in times of need. The triangle also makes space for an individual to choose to be surrounded by others or to find themselves in a more acute and solitary position, all the while still being supported.

An Abrome Learner's learning community is comprised of intellectually curious Learners, committed Learning Coaches, and a personal network that is standing by ready to lend their support.

Psychological Safety:

The overlap between well-being and the learning community represents psychological safety.

Abrome is a psychologically safe space where young people feel free to engage in unlimited free play, and take intellectual and personal risks without fear of being assessed, judged, or ridiculed. The ability to remain vulnerable in the pursuit of growth is an extension of our focus on well-being coupled with a learning community that values diversity.

Learning and Inquiry:

The overlap between self-directed learning and the learning community represents learning and inquiry.

At Abrome, self-directed Learners leverage a dynamic and diverse learning community to engage in deep, meaningful, and enduring learning experiences. Connection with others is valued. Collaboration, debate, and peer learning are outcroppings of a culture that values mentorship and dialectical inquiry.

Meaningfulness:

The overlap between self-directed learning and well-being represents meaningfulness.

Given the time and space to focus on their well-being and engage in self-directed learning, Abrome Learners come to understand themselves and how they fit into the world. They find significance in creating connections with others and contributing to something beyond themselves. Abrome Learners develop lives that have purpose, value, and impact.

Emancipated Learning:

The interplay between psychological safety, learning and inquiry, and meaningfulness represents emancipated learning.

Abrome Learners feel comfortable taking risks and diving deep in pursuit of knowledge in their fields of interests, rather than skimming them at the surface. Learners construct knowledge by leveraging resources that are directly available to them, to include their learning community, or by acquiring necessary resources in the process of exploration and discovery. This process is unique for every Learner as they link various resources, in pursuit of their own purposes, according to their own needs. Like any two distinct individuals, no two Learners or educational pathways are the same; only in retrospect will a learning pathway become fully defined. When an individual is able to marry such educational experiences with a life of meaning, the result is a remarkable life lived.

Education should be a liberating experience that allows people to lead remarkable lives so they can positively impact society and improve the human condition. Education fads and supplemental experiences do not unwind the oppression of schooling. Emancipated Learning, however, allows anyone to leverage their education so that they can lead a remarkable life.