Tuesday was day 102 of the pandacademic year, and that morning I woke up and worked on the blog post for day 100 of this pandacademic year. I got distracted a bit and tinkered with the website. For those who do not know, Abrome is a Self-Directed Education community. We are members of the Agile Learning Center community, Flying Squads, and the Alliance for Self-Directed Education. I updated the website so that each of these were represented on the front page. I’ve only been meaning to do that for over a year now.

When I arrived at Abrome later that morning I got to hand out copies of Usual Cruelty: The Complicity of Lawyers in the Criminal Injustice System by Alec Karakatsanis to everyone who committed to reading and discussing it. The author’s publisher, The New Press, was offering to give free copies to educators and we jumped on it. We will begin to read it this week and we have our first discussion planned for Friday.

When it was time for the morning meeting one of the Learners opted to be the gameshifter and had us sit or stand, and use popcorn to participate in the meeting. Building off the conversation for the day prior, we each shared something about Self-Directed Education that we appreciate or value: freedom to be a little human, being able to wander, Learners not spending energy focused on pleasing adults, instead of someone teaching you you get to freely learn, freedom of speech, safe space, freedom to do anything you please (except murder or things that get you in trouble [later rephrased to except anything that hurts others]), and I don’t have to make lesson plans. That last one was Facilitator Ariel’s contribution.

The meeting went really well and it seemed we were going to have a really good day. Everyone had shown up and the weather was great and people seemed energized. I asked anyone if they wanted to join me in the morning hike and they all passed, so I went up by myself and jumped on a call with the remote Learners. Then I came back down and joined the rest of the crew at the lake, where they most often choose to spend their day.

Reading Usual Cruelty

It was a busy day at the lake as the Learners were engaged in a wide variety of activities. Some of the activities included a couple of Learners riding the bikes that they brought that day, one of the Learners reading their copy of Usual Cruelty, and multiple Learners discussing water births. As for reading outdoors, it is something that all Facilitators and several Learners do at times. While I thoroughly enjoy reading indoors, I am also a big fan of reading outdoors. There’s just something wonderful about being able to dive into a great book when the sun is not too bright and there is a very gentle breeze. I highly recommend it.

Learners checking out video edits

Facilitator Ariel was working on some video edits of the GoPro footage that was taken earlier in the week. He showed some of the Learners the progress he had made on editing the videos, and one of the Learners asked to go deeper in the conversation so that she could also edit some video. They edited some video together, and then Facilitator Ariel gave her some of his footage that she wanted to work on. We will probably upload the product of that initial conversation on our YouTube channel.

Over at the other cell Facilitator Lauren and the younger Learners were having a less easygoing day. For one, the Learners were getting pretty tired of the tick situation. Facilitator Lauren has tried to educate the Learners (and Facilitators) on the presence of ticks, how to protect against them, and how to check for them.

Climbing rocks within safety limits

Also, it was a rough day in terms of safety boundaries. As you know if you have been following us for a while, we want Learners to exist autonomously while at Abrome, but we must also keep them safe. For example, Learners are free to roam, but we are not going to let them play in the middle of a highly trafficked road, or allow them to play on the top of a moss covered dam with water flowing over it. Facilitator Lauren set some safety boundaries on climbing up on higher altitude rocks on this day and the Learners went past it, and this resulted in a difficult situation with Facilitator Lauren asking the Learner to please come down while the Learner protested. It led to difficult conversations afterward about why safety boundaries exist even if we are not a schoolish community. Testing our limits is a good thing, but there are limits to what counts as reasonable limits.

Additionally, the wind that day was a challenge, and a big gust of wind kicked up a lot of dirt and blew it into one of the Learner’s eyes. This is the same Learner who got a really nice cut on his foot thanks to a zebra mussel several months ago, and short of a really tough incident he rarely chooses to go home. But on this day, he chose to go home. That’s just the type of day it was at the other cell.

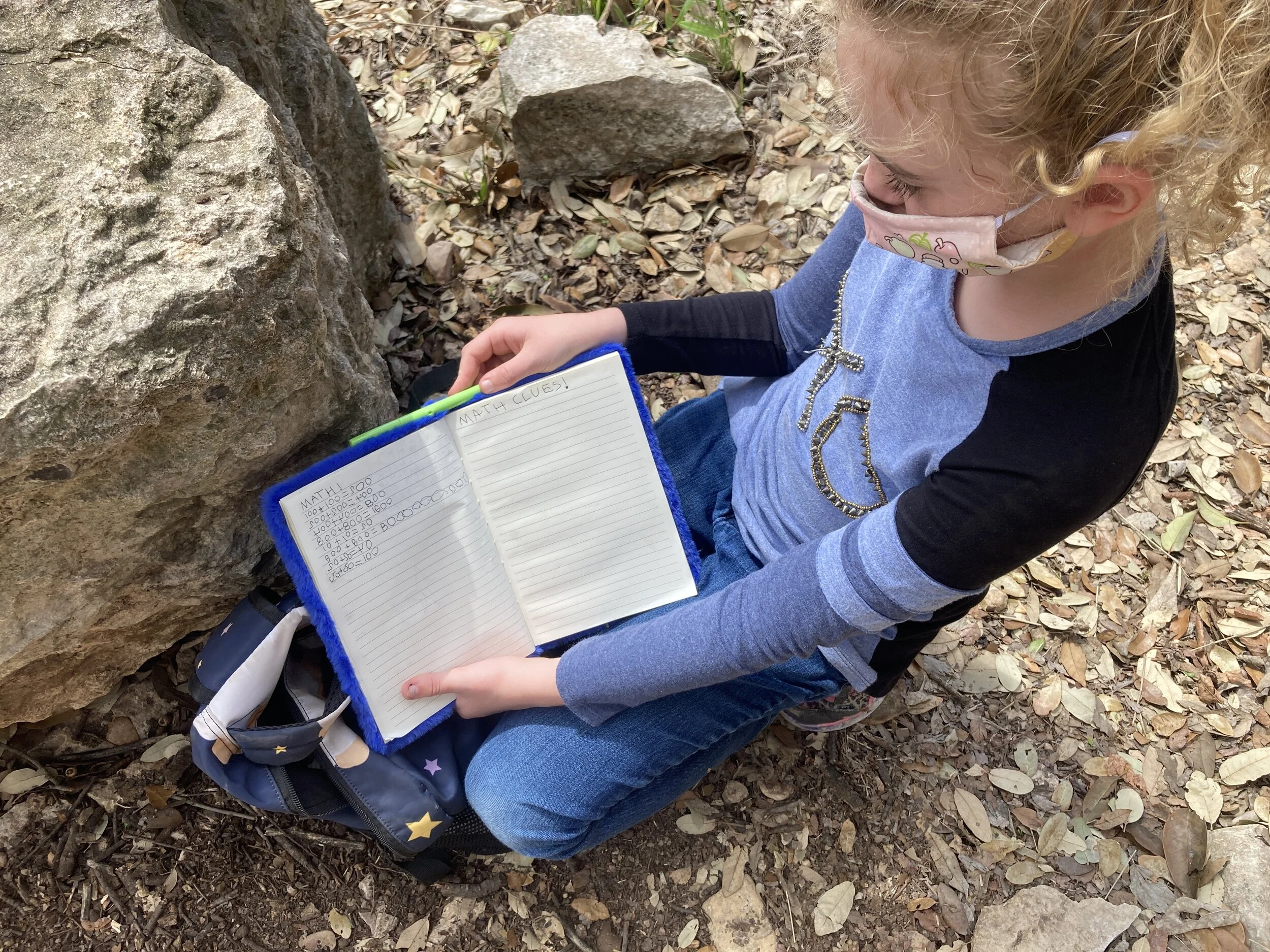

Furry blue journals are great for math

But it wasn’t all difficult. There was still plenty of play in between the more challenging moments. There was imaginative nature play, and one of the Learners broke out her brand new, furry blue journal where she played with math.

And no, she wasn’t encouraged to do so. At Abrome we don’t try to nudge the Learners to read, write, or do math, much less engage in more advanced academics. We want them to pursue their interests no matter the domain and no matter if it is academically valued in a schooled society. When they want to learn to read or do math then we are happy to be supportive, and we try to cultivate a culture of literacy and numeracy through modeling and psychological safety. But the thing is, all the Learners learn to read, write, and do arithmetic. It is just the way humans are—because it is socially valued they want to learn it. And they do, on their terms, on their timeline.

Back at Abrome I ventured out to the dock where several of the Learners were in conversation and one of the Learners asked me about what it would take for us to be allowed to meet at the Abrome facility, again. He had never even been there because he joined at the beginning of the pandacademic year. I reminded him that we would not be able to do so until we hit pandemic risk stage level 1 in the local region, and that would not likely happen until the summer at the earliest. Further, I added, it may only be an option for those who have been fully vaccinated, and that I would be reviewing the policies over spring break. The conversation allowed us to talk about the effectiveness of the vaccines and the likelihood that it would become available to the Learners by the end of the year.

Later, a group of fisherman showed up to fish on the dock so the Learners cleared out. While we were hanging out nearby, two of the fisherman left for some reason and the remaining fisherman cried out for help. Turns out he was an inexperienced fisherman and he caught a fish. Two Learners approached him, asked him if he needed help, and he said he did. One then assisted in reeling it in, while the other walked him through the steps of how to grab a fish. It was a fun experience for all involved. After that the Learners talked about doing some fishing of their own, in the future.

Captivating conversations

Toward the end of the day one of the Learners asked me if the term “super straight” was transphobic. Turns out that it is a term that is used to self-identify as someone who is straight, and could never possibly be attracted to or date a trans person. It was an interesting question that led us down the path of the implications of using such a term, the different contexts that it might be used in, and whether or not it was even possible to be “straight” to such a degree that it was impossible to be attracted to a trans person. After considering the issue I came to the opinion that it was a transphobic term, regardless of the intentions of the person who uses it, and regardless of the intention behind the creation of the term. I appreciated the opportunity to think about it in an open way, looking at all sides of the possible argument, even if some may be repugnant, and doing so in a way that centered the humanity of trans people. And yeah, “super straight” is most certainly a transphobic term.

After the afternoon roundup and after the Learners all went home the Facilitators had a long after action review where we talked about the events of the day, and some of the real struggles of the day. Self-Directed Education is not always pretty, and sometimes it is downright messy. Sometimes feelings get hurt, and sometimes people get frustrated and frazzled. But that is the cost of freedom. And at the end of the day, we will take a messier freedom than a more orderly form of control.